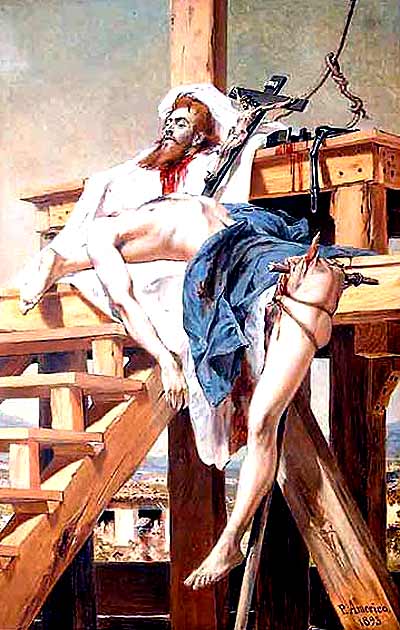

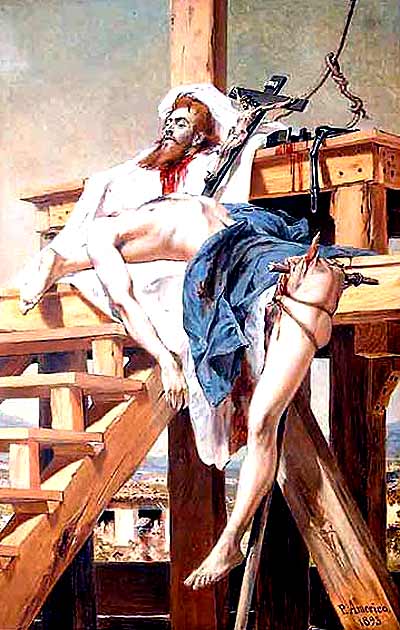

O painting Tiradentes Esquartejado, by Pedro Américo (1843-1905), was for four years the “interlocutor” of historian Maraliz de Castro Vieira Christo. The researcher maintained, in her words, an exercise in looking at the work, engaging in a “particularized dialogue” with the painting. The meanings, in this case, are not figurative. This coexistence resulted in the thesis “Painting, history and heroes in the XNUMXth century: Pedro Américo and Tiradentes Esquartejado”, winner of the Capes Grand Prize for Theses “Florestan Fernandes”.

O painting Tiradentes Esquartejado, by Pedro Américo (1843-1905), was for four years the “interlocutor” of historian Maraliz de Castro Vieira Christo. The researcher maintained, in her words, an exercise in looking at the work, engaging in a “particularized dialogue” with the painting. The meanings, in this case, are not figurative. This coexistence resulted in the thesis “Painting, history and heroes in the XNUMXth century: Pedro Américo and Tiradentes Esquartejado”, winner of the Capes Grand Prize for Theses “Florestan Fernandes”.

The supervisor of the work, Jorge Coli, professor at the Institute of Philosophy and Human Sciences (IFCH) at Unicamp, where the thesis was defended, classified the research as “exceptional”, an opinion that, moreover, confirms the fact that the thesis was chosen as the best of the year in the major area of Human Sciences. Maraliz's contact with the work of the painter from Paraíba introduces several new elements into the history of Brazilian art. The author visited museums, searched documents and explored areas such as literature, history, journalism, visual arts, politics, among others.

The historian, who is a professor at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora, observes that, in Brazil, there is a certain difficulty in promoting this exercise of observation due to the lack of tradition. In Maraliz's opinion, most Brazilian art history research, on the one hand, focuses on the formal elements of the painting – which she considers necessary –, or, on the other extreme, practically excludes the work from its analysis and partly for a sociological contextualization. “We historians, when we analyze an artistic object, have a tendency to take peripheral approaches, focusing on the training of artists, criticism or the market. We fear dialogue with the work, even because this requires erudition in the history of art, which is difficult to acquire in Brazil”, she acknowledges.

Maraliz reveals that he was concerned with moving between the historiographic and imagery fields, always trying to have the work as a reference, without losing sight of it. “I worked in a multiple way, always inserting the painting in other contexts, searching for the cultural substrate that engendered the representation of dismemberment. I didn't use the painting as a subterfuge. I am not studying the Conjuration, but a painting.”

The choice of Pedro Américo's work was not random. In Maraliz's opinion, the painting is a unique case in the history of Brazilian and Western art for privileging the vision of quartering. By opting for this, observes the author of the thesis, Pedro Américo ignored consolidated parameters of the history of art and, mainly, of historical painting, including the notion of the beautiful ideal of the body. “The vision of violence on the body is not typical of historical painting. The artist was very courageous, especially if we think that at that time Tiradentes was asserting himself as a national hero”, says Maraliz.

In the tradition of historical painting, the historian teaches, the artist invariably chose a moment that revealed the hero's grandeur. This character was represented in the action through which his name would be immortalized in history; the artist would choose the most “precious” moment of this action. This kind of snapshot, continues Maraliz, would allow the viewer to remember the before and after of that story. “By showing the dismemberment, Pedro Américo suppresses the aftermath, emphasizing the aggression of the colonial system more than the hero’s virtues”, she compares.

The thesis is divided into five chapters. The first deals with the circulation of the work. Pedro Américo made the painting in 1893, in the Italian city of Florence, where he lived. During this period, the artist was elected constituent deputy for Paraíba. He returns to Brazil and exhibits the painting in Rio de Janeiro, in July 1893. As the painting is not well received, he exhibits it in Juiz de Fora, which decides to buy the work. During this period, collector Alfredo Ferreira Lage, creator of the Mariano Procópio Museum and owner of a large collection, was a councilor in the municipality. “I raise, in the thesis, the hypothesis that Lage, whose collection gave rise to the museum, influenced the purchase of the painting.”

Maraliz bets on originality, starting with the inversion of the temporal order, that is, the author begins by talking about the Brazil 500 Years Exhibition, held at the Ibirapuera Museum, in São Paulo, where the painting was exhibited, and goes back in chronology. Along this path, the historian addresses the appropriation made in the 1970s by artists Wesley Duke Lee, Arlindo Daibert and Sandro Donatello Teixeira.

Maraliz bets on originality, starting with the inversion of the temporal order, that is, the author begins by talking about the Brazil 500 Years Exhibition, held at the Ibirapuera Museum, in São Paulo, where the painting was exhibited, and goes back in chronology. Along this path, the historian addresses the appropriation made in the 1970s by artists Wesley Duke Lee, Arlindo Daibert and Sandro Donatello Teixeira.

It also shows how Tiradentes Esquartejado, after remaining 70 years in the Juiz de Fora museum, almost forgotten, was incorporated, in 1969, by mass culture from the encyclopedia “Grandes Characteragens da Nossa História”, launched by Abril and originally designed to place Brazilian military heroes in the pantheon. These do not escape the astuteness of Maraliz, who mentions the fact that the mythical figure of Tiradentes was exploited both by the epigones of the dictatorship and by left-wing cadres, including Getúlio Vargas, among others.

The fact that the painting was circulated in installments sold on newsstands is far from placing it as a public success. For comparison purposes, Maraliz cites another painting by Américo, O Grito do Ipiranga, which was reproduced shortly after its production, in 1888, and continued to be published extensively on the most varied media, from trays to clocks, especially at the time of the centenary of Independence. “Reproductions of Tiradentes Esquartejado are rare. The first one I found was in the biography of Pedro Américo made by his son-in-law, ambassador Cardoso de Oliveira, in 1943, fifty years after his exhibition in Rio de Janeiro. Not being reproduced, not circulating as an image, the painting, forgotten, did not help to build the myth of Tiradentes at the time”.

Narrative – One of the greatest revelations of Maraliz's work is in the second chapter of the thesis. The historian discovered, through an article written by Pedro Américo for a Rio newspaper, that Tiradentes Esquartejado was part of a narrative of five paintings about the Conjuração Mineira. Pedro Américo names the series. The discovery is a great contribution to the understanding of the work that is at the center of the thesis.

The first frame of the narrative shows the poet Tomás Antonio Gonzaga embroidering his bride's dress with gold thread. The second brings to light the most important meeting held by the conspirators. The third would show the passing of the death certificate in front of the corpse of Cláudio Manuel da Costa. The fourth would be the Tiradentes prison, and the fifth is Tiradentes Esquartejado. Maraliz found oil studies of the reunion of the conspirators and Tiradentes Esquartejado. The first was in the house of the painter's descendants in Florence, where Américo kept his studio and died. The second is in the city of Novo Hamburgo in Rio Grande do Sul. The rest were studied based on the article authored by the writer.

The first frame of the narrative shows the poet Tomás Antonio Gonzaga embroidering his bride's dress with gold thread. The second brings to light the most important meeting held by the conspirators. The third would show the passing of the death certificate in front of the corpse of Cláudio Manuel da Costa. The fourth would be the Tiradentes prison, and the fifth is Tiradentes Esquartejado. Maraliz found oil studies of the reunion of the conspirators and Tiradentes Esquartejado. The first was in the house of the painter's descendants in Florence, where Américo kept his studio and died. The second is in the city of Novo Hamburgo in Rio Grande do Sul. The rest were studied based on the article authored by the writer.

The narrative proposed by Américo, explains Maraliz, has a tragic structure if the choices made by the artist to represent the Conjuração Mineira are taken into account. The fact that the series begins by showing Gonzaga embroidering, continues the historian, is a very strong way of representing who would be the main intellectual mentor of the conspiracy. The poet was sentenced from the beginning of the movement, but not to death, as his involvement was not proven. “The evidence was circumstantial and he was the only one who never admitted to having participated in the conspiracy”, recalls the historian.

Passionate poet – Gonzaga, reveals the author of the thesis, made two mentions of embroidery during his lifetime. The first, in one of the lyrics from the book Marília de Dirceu, in which she describes the dream she had, where she saw herself embroidering her bride's dress. The other is in the case records, when asked in one of the interrogations about his participation in the movement, Gonzaga said that, even though people were talking about the revolt at the table in his house, he wasn't paying attention because he was embroidering in a corner. “Gonzaga uses this argument to exempt himself from any guilt, presenting himself as a passionate poet, with no head to think about conjurations, but only about his Marília”.

The historian investigated what was said about the poet in the 19th century. When consulting anthologies, biographies and the various editions of Marília de Dirceu, she found some changes in the construction of Gonzaga's image. At the beginning of the century, for example, he was seen as the innocent poet who was caught up in the conspiracy by his friends. “The authors used this 'being embroidered' to disqualify him as a conjuror”, says the historian. “When Pedro Américo begins his narrative with Gonzaga embroidering, he is also disqualifying the conspirator, to the same extent that he values the poet”.

In the second half of the century, from 1850 to 1870, more precisely after the publication of the Chilean Letters, Gonzaga began to be seen as the leader of the movement. Its share price, however, began to fall due to the advent of the republican movement, whose ideas placed Tiradentes as the great leader.

In the second frame, the focus is on the reunion of the conspirators. It is, according to Maraliz's description, a night scene in which the conspirators appear in a room around a table. Everyone looks at Tiradentes, highlighting him at one end of the table. At the other end, according to the historian, is Silvério dos Reis. The action of the conspirators is perplexing. “Reticent, they listen to Tiradentes. Our memory reminds us that Silvério dos Reis is the traitor, making us aware of what is happening: Tiradentes trusts the conspirators too much, without realizing that some of them may betray him. Pedro Américo shows us not only the act of conjuring, but the mistake made by the hero. An error that caused the tragedy of the prisons and his own execution.”

The third narrative is the scene in which Cláudio Manoel da Costa appears dead. It is not known whether it was murder or suicide, recalls Maraliz, but he died because he talked too much. “Either he regretted what he said and committed suicide or was killed before he could incriminate anyone else.” The fourth narrative is that of Tiradentes in prison. The hero of the Inconfidência remained confined for three years. It is speculated that he underwent a transformation during this period. The writer Joaquim Norberto, widely read by Pedro Américo, even wrote, Maraliz notes, that “they had arrested a patriot and executed a friar”. Finally, in the last and best-known of the paintings, Tiradentes appears dismembered.

In the historian's opinion, the structure of the narrative embodies a logic: it brings a lyrical beginning [Gonzaga embroidering], Tiradentes' mistake in trusting the conspirators and, finally, the catastrophe of repression caused by the hero's error. “It is a tragic narrative and not a grandiloquent one. If it were an affirmative speech, he would not begin it with Gonzaga embroidering, but rather with the poet writing the laws of the new Republic; and much less would it present the dismemberment as the final scene”. Maraliz also draws attention to the fact that the narrative has no vision of the future. “The dismemberment prevents the resurrection of the character’s ideals, fixes us in death, unlike, for example, the narrative about Conjuração Mineira made by Portinari, which, despite representing the dismembered body, projects future freedom as a possibility”.

Contextualizing, Maraliz remembers that the Republic, recently implemented, was proposing a line of continuity – Conjuração Mineira, Independence and Republic. “Pedro Américo does not corroborate this idea, even more so if we observe that the formal structure of the painting causes our gaze to stay between the dismembered head and that skewered leg”, he observes. “Our gaze is not fixed on the luminous sky, foreseeing a future, it is retained on the concreteness of the corpse, of death.”

Contextualizing, Maraliz remembers that the Republic, recently implemented, was proposing a line of continuity – Conjuração Mineira, Independence and Republic. “Pedro Américo does not corroborate this idea, even more so if we observe that the formal structure of the painting causes our gaze to stay between the dismembered head and that skewered leg”, he observes. “Our gaze is not fixed on the luminous sky, foreseeing a future, it is retained on the concreteness of the corpse, of death.”

According to what the author of the thesis found, the representation proposed by Pedro Américo is critical in relation to the Conjuração Mineira movement. In part, the artist's disbelief in the face of the revolt arose from reading the book “A História da Conjuração Mineira”, by Joaquim Norberto, accused at the time of presenting a monarchist vision of the historical fact. “The book was lent to him by the Baron of Rio Branco”, reveals the historian, for whom it is not possible to say whether Pedro Américo was a monarchist or a republican.

“He was a close friend of the imperial family, who always supported him. It was the emperor, in fact, who discovered him, financed his travels, his training at the Paris School of Fine Arts and made him the official painter of the Empire. However, his biographer and son-in-law maintained that he was a Republican.” For the author of the thesis, Américo's political convictions do not explain his work. “I think he saw himself more like Baudelaire, as an intellectual imbued with a civilizing mission, placing himself above the political struggle. Deep down, he really hated the Brazilian political elite. This is clear in his novel Holocaust.”

Naive – Pedro Américo, from what Maraliz found, did not have faith in the Conjuration as a concrete possibility at that historical moment – the end of the 18th century. In a letter addressed to Barão do Rio Branco, the artist wrote that Tiradentes was unaware of himself or the world in which he was living. “I have the impression that Pedro Américo did not believe in the revolutionary capacity of the conspired intellectuals, much less in Tiradentes, who he believed to be naive. The painting, before denouncing colonial repression, exposes the hero’s fragility.”

Another great advance that Maraliz makes in the study of the painting is in the third and fourth chapters, in which the teacher not only places the work in Pedro Américo's historical painting but also shows how the Brazilian painter's work as a whole is placed in historical painting International. “I had to enter several contexts”, says the historian. “It was necessary to understand how a painter offers the newborn Republic a shattered hero.”

Maraliz promotes an accurate reinterpretation of two paintings by Pedro Américo about the Paraguayan War: Batalha de Campo Grande, which introduced him to historical painting and is in the Imperial Museum of Petrópolis, and Batalha do Avaí, which is in the National Museum of Fine Arts , in Rio, in addition to focusing on other works. In both battles, the author draws attention to the uncomfortable situation of the heroes. “In the Battle of Campo Grande, the Count d'Eu appears mounted on his white horse, but without any expression, protected by his assistants against an enemy attack. In the Battle of Avaí, Caxias and Osório are lost amid the chaos of the battle.”

The historian avoided working with the idea of movement or schools. She first carried out a study of Pedro Américo's teachers, to see if there was any resonance in his work and, later, she sought to discover the cultural, artistic and sensitivity affinities that the painter maintained with his time. “I avoided labels or imprisoning him inside a school. My research sought exactly to try to understand how his works worked. If I label it in advance, I can’t see this richness.”

The historian crossed borders. Through a scholarship granted jointly by the Getty Foundation and the National Institute of Art History in Paris, she spent a year researching in France and Italy, to get a feel for the Brazilian painter's references. Maraliz studied, for example, the way in which artists constructed the figure of the national hero. In these representations, great actions always stand out, an affirmative speech by the hero. “Several of them died in pieces, but I didn’t find this representation anywhere. The shattered body was only presented in Christian martyrdom. Even though Pedro Américo’s painting brings political martyrdom closer to Christian martyrdom, the painting is not limited to that.”

On the other hand, in her investigation of the international situation at the time, the historian found that, not infrequently, history painters from Pedro Américo's generation, such as the French Henri Regnault (1843-1871), Georges Clairin (1843-1919) , Paul-Joseph Jamin (1853-1903) and Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse (1859-1938) sublimated violence, presenting scenes from world history in Paris exhibitions where aggressors slaughtered their victims. Maraliz also remembers that historical painting from the second half of the 1798th century has only been studied and valued now. For modernists, points out the author of the thesis, this aspect stopped at [Eugène] Delacroix (1863-XNUMX).

On the other hand, in her investigation of the international situation at the time, the historian found that, not infrequently, history painters from Pedro Américo's generation, such as the French Henri Regnault (1843-1871), Georges Clairin (1843-1919) , Paul-Joseph Jamin (1853-1903) and Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse (1859-1938) sublimated violence, presenting scenes from world history in Paris exhibitions where aggressors slaughtered their victims. Maraliz also remembers that historical painting from the second half of the 1798th century has only been studied and valued now. For modernists, points out the author of the thesis, this aspect stopped at [Eugène] Delacroix (1863-XNUMX).

In the fifth chapter, the historian examines issues linked to sensitivity to the dismembered body. She collects what critics said about the painting, what arguments were involved in the controversies and, mainly, rereads the dialogue between Barão Homem de Mello and the academy's aesthetics professor Carlo Parlagreco. “I explore the universe of aesthetics, the beautiful ideal, the pedagogical function of a historical painting. Pedro Américo's contemporaries said that the picture was very well painted, but that a hero could not be shown in pieces. For them, it was not a historical painting, but rather a vision of anatomy, of butchery. This refusal of criticism caused what we highlighted at the beginning of the thesis: the forgetting of the painting”.

There was, according to Maraliz, a divorce between two worlds – the European and the Brazilian. “The decadent sensibility of the late 19th century privileged the aesthetics of horror. The French were attracted to violence as a spectacle, whether in the Théâtre du Grand-Guignol, in literature, especially if we remember Octave Mirbeau's book Garden of Torments, or in the trade in photographs whose theme was the destroyed body, particularly those revealing torture Chinese. In this context, Pedro Américo's painting could even be well received. While in France they no longer believed in their own heroes, Brazil was building its republican pantheon”, says Maraliz, recounting part of our history.

Read also Coli's perspective on the History of Art

O painting Tiradentes Esquartejado, by Pedro Américo (1843-1905), was for four years the “interlocutor” of historian Maraliz de Castro Vieira Christo. The researcher maintained, in her words, an exercise in looking at the work, engaging in a “particularized dialogue” with the painting. The meanings, in this case, are not figurative. This coexistence resulted in the thesis “Painting, history and heroes in the XNUMXth century: Pedro Américo and Tiradentes Esquartejado”, winner of the Capes Grand Prize for Theses “Florestan Fernandes”.

O painting Tiradentes Esquartejado, by Pedro Américo (1843-1905), was for four years the “interlocutor” of historian Maraliz de Castro Vieira Christo. The researcher maintained, in her words, an exercise in looking at the work, engaging in a “particularized dialogue” with the painting. The meanings, in this case, are not figurative. This coexistence resulted in the thesis “Painting, history and heroes in the XNUMXth century: Pedro Américo and Tiradentes Esquartejado”, winner of the Capes Grand Prize for Theses “Florestan Fernandes”.  Maraliz bets on originality, starting with the inversion of the temporal order, that is, the author begins by talking about the Brazil 500 Years Exhibition, held at the Ibirapuera Museum, in São Paulo, where the painting was exhibited, and goes back in chronology. Along this path, the historian addresses the appropriation made in the 1970s by artists Wesley Duke Lee, Arlindo Daibert and Sandro Donatello Teixeira.

Maraliz bets on originality, starting with the inversion of the temporal order, that is, the author begins by talking about the Brazil 500 Years Exhibition, held at the Ibirapuera Museum, in São Paulo, where the painting was exhibited, and goes back in chronology. Along this path, the historian addresses the appropriation made in the 1970s by artists Wesley Duke Lee, Arlindo Daibert and Sandro Donatello Teixeira.  The first frame of the narrative shows the poet Tomás Antonio Gonzaga embroidering his bride's dress with gold thread. The second brings to light the most important meeting held by the conspirators. The third would show the passing of the death certificate in front of the corpse of Cláudio Manuel da Costa. The fourth would be the Tiradentes prison, and the fifth is Tiradentes Esquartejado. Maraliz found oil studies of the reunion of the conspirators and Tiradentes Esquartejado. The first was in the house of the painter's descendants in Florence, where Américo kept his studio and died. The second is in the city of Novo Hamburgo in Rio Grande do Sul. The rest were studied based on the article authored by the writer.

The first frame of the narrative shows the poet Tomás Antonio Gonzaga embroidering his bride's dress with gold thread. The second brings to light the most important meeting held by the conspirators. The third would show the passing of the death certificate in front of the corpse of Cláudio Manuel da Costa. The fourth would be the Tiradentes prison, and the fifth is Tiradentes Esquartejado. Maraliz found oil studies of the reunion of the conspirators and Tiradentes Esquartejado. The first was in the house of the painter's descendants in Florence, where Américo kept his studio and died. The second is in the city of Novo Hamburgo in Rio Grande do Sul. The rest were studied based on the article authored by the writer. Contextualizing, Maraliz remembers that the Republic, recently implemented, was proposing a line of continuity – Conjuração Mineira, Independence and Republic. “Pedro Américo does not corroborate this idea, even more so if we observe that the formal structure of the painting causes our gaze to stay between the dismembered head and that skewered leg”, he observes. “Our gaze is not fixed on the luminous sky, foreseeing a future, it is retained on the concreteness of the corpse, of death.”

Contextualizing, Maraliz remembers that the Republic, recently implemented, was proposing a line of continuity – Conjuração Mineira, Independence and Republic. “Pedro Américo does not corroborate this idea, even more so if we observe that the formal structure of the painting causes our gaze to stay between the dismembered head and that skewered leg”, he observes. “Our gaze is not fixed on the luminous sky, foreseeing a future, it is retained on the concreteness of the corpse, of death.”  On the other hand, in her investigation of the international situation at the time, the historian found that, not infrequently, history painters from Pedro Américo's generation, such as the French Henri Regnault (1843-1871), Georges Clairin (1843-1919) , Paul-Joseph Jamin (1853-1903) and Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse (1859-1938) sublimated violence, presenting scenes from world history in Paris exhibitions where aggressors slaughtered their victims. Maraliz also remembers that historical painting from the second half of the 1798th century has only been studied and valued now. For modernists, points out the author of the thesis, this aspect stopped at [Eugène] Delacroix (1863-XNUMX).

On the other hand, in her investigation of the international situation at the time, the historian found that, not infrequently, history painters from Pedro Américo's generation, such as the French Henri Regnault (1843-1871), Georges Clairin (1843-1919) , Paul-Joseph Jamin (1853-1903) and Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse (1859-1938) sublimated violence, presenting scenes from world history in Paris exhibitions where aggressors slaughtered their victims. Maraliz also remembers that historical painting from the second half of the 1798th century has only been studied and valued now. For modernists, points out the author of the thesis, this aspect stopped at [Eugène] Delacroix (1863-XNUMX).